HISTORY

Hans Miedler Fine Art’s location reflects in an incomparable way the change that has taken place over four centuries. The rise and decline of family dynasties, the flourishing of the first wholesale houses, the social boom of the manufacturers and their resulting position in society, as well as the emergence of the first private banks.The interdependencies of the European aristocratic houses are also clearly reflected here. This story doesn’t aim to be complete but rather a delicate guide through a bygone era.

Prolog

For a long time now, I have been thinking about writing down the history of the place I have had the pleasure of residing at for many years. With such a long history and so many personalities at hand, a short summary has not proven easy. If you included all the characters who have lived, loved, celebrated, danced, made music or found their final resting place within these walls, you could write a whole book.

This place reflects in an incomparable way the change that has taken place over four centuries. The rise and decline of family dynasties, the flourishing of the first wholesale houses, the social boom of the manufacturers and their resulting position in society, as well as the emergence of the first private banks.The interdependencies of the European aristocratic houses are also clearly reflected here. This story doesn’t aim to be complete but rather a delicate guide through a bygone era.

If you can take some time, just a little moment from your otherwise busy everyday life, then I invite you to take a walk through the history of this special place with me. For the current friends of our art house and for those who will be in the future.

Yours,

Hans Miedler

A place with history, a house, its owners, over more than four centuries

Palais Fries — Pallavicini, its history over the changing time

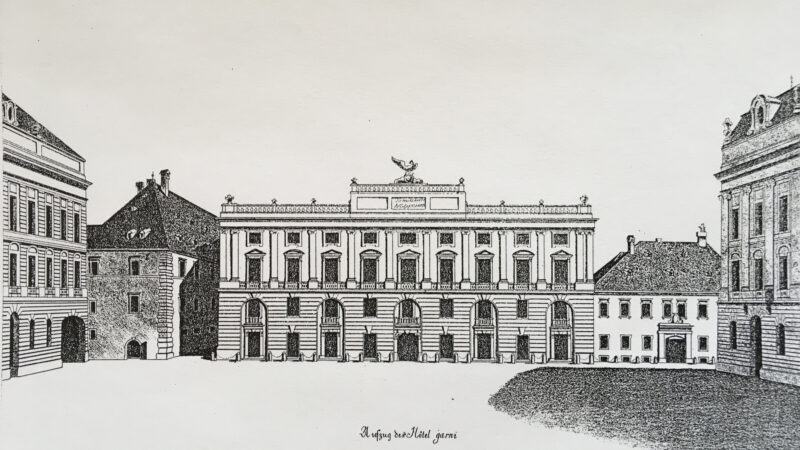

The Palais Pallavicini, formerly Palais Fries, is located opposite the ensemble of the Vienna Hofburg, alongside the Spanish Riding School, the National Library and the Augustinian Church on one of the city’s most important squares, Josefsplatz.

Its eponymous name came from Emperor Josef II, the son of Maria Theresa, whose large equestrian statue, which was made in the style of Marc Antony in Vienna, forms the center of the square.

In the early 16th century, more precisely 1529, the place where Palais Fries — Pallavicini stood was the residence of Nicholas, Count of Salm (1459 — 1530), the reigning count of Neuburg and a general of the Renaissance. At the age of 17, Nicholas, Count of Salm took part in the Battle of Murten against Charles the Bold, the Duke of Burgundy, in 1476. In 1488 he fought in Flanders, and from 1491 he was the chief Imperial captain. In 1509 he fought under Georg von Frundsberg in Italy and subsequently conquered Istria. In 1525 Nicholas, Count of Salm was involved in the capture of King Francis I of France in the Battle of Pavia, and in 1526 he controlled the Peasants’ Revolt in Tyrol and conquered Schladming. In 1529 he was in command of the first Turkish siege in Vienna and organized the successful defense of the city, which made him famous in the Habsburg Empire. The strains of the many battles and an injury sustained defending Vienna finally led to his death in 1530. His brother Hektor sold the city palace to Emperor Ferdinand I in 1559 and he bequeathed it to his son Charles II, Archduke of Austria (1540−1590).

His niece Archduchess Elisabeth of Austria (1554 — 1592), the second oldest daughter of Emperor Maximilian II (1527−1576, Emperor from 1564) and Mary of Spain (1528 – 1603), the daughter of Emperor Charles V (1500 – 1558) subsequently acquired it.

Elisabeth grew up in a large group of siblings and like her brother, Emperor Rudolf II, she received a very good education, although her mother’s influence was particularly noticeable in her very strict religious upbringing. Elisabeth recognized her calling to care for the poor and the sick at a young age, like her patron saint Elisabeth of Thuringia.

As a young girl, and already celebrated as one of the most beautiful princesses in Europe, Elisabeth was promised, as was customary at the time, to Charles, the second-born son of the French king Henry II and Catherine de’ Medici. It was Catherine who wanted to win this intelligent and noble princess as a wife for her son. She started the negotiations, which lasted nine years, in 1561.

The wedding took place on October 22, 1570 per procuram in Speyer. The representative of the French king was her uncle Archduke Ferdinand of Further Austria, who, among other things, was rewarded with the world famous Saliera of Benvenuto Cellini, that is proudly exhibited in Vienna’s Kunsthistorische Museum today.

The wedding of the 16-year-old Archduchess Elisabeth to the 20-year-old Charles IX, King of France, took place in Mézières in the Champagne region. With her shiny retinue, the archduchess headed for Mézières. On the way there, her brother Charles, the Duke of Anjou, was waiting for her in Sedan to continue the journey together. King Charles IX was expected to meet her in Mézières but was so curious that it is said that he travelled to Sedan in disguise to secretly see Elisabeth. From the first moment he saw her he was enchanted by her beauty and grace. Charles was often quoted as having said that he not only had the purest, most virtuous wife in France and Europe, but in the whole world.

The coronation ceremony was held at the Basilica Cathedral of Saint Denis on March 25, 1571. The marriage led to the birth of their daughter Marie Elisabeth (1572 – 1578). Throughout his life, King Charles IX was a mentally unstable and influenceable ruler, who was under the constant influence of his mother Catherine. In order not to lose her influence on the young king and to assert herself against her adversaries, Catherine forced him to agree to the scheme on the night of August 23, 1572, the so-called St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre of the French Protestants. Elisabeth was kept away from any influence on the young king by Charles’ mother and was not really proficient in the French language, the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre haunted her for the rest of her life.

The catastrophic decisions that led to the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre were kept secret from the young queen. When the news of what had happened was brought to her, she asked with horror: “Does the king know, my husband?” And exclaimed: “Who gave him such advice? Forgive him, O God, and be gracious to him, otherwise this sin will never be forgiven.” Even Charles, who was already suffering from tuberculosis at the time, was deeply horrified by the events of that night and the days that followed. Charles died on May 30, 1574, at the age of 24, cared for by Elisabeth compassionately.

After Charles’ death, Elisabeth received a large number of marriage proposals, all of which she declined in memory of her royal husband. She focused her attention on her daughter, Marie Elisabeth, and a large number of charitable projects. Following the death of her 5‑year-old daughter, whom she had transferred all her motherly care and love to, she returned to Vienna alone. She was given a festive welcome by her brother Emperor Rudolf II

In 1582 she founded the “Queen Monastery” or “Monastery of the Angels” on the property acquired by her uncle and expanded by further investment and donations, to accommodate 60 Clarissans. From then on, it existed as such for exactly 200 years until Joseph II abolished it due to the reforms.

The monastery preserved some religious art treasures and relics during the 200 years of its existence. The founder herself was buried in the monastery church, built between 1582 and 1583, as well as the remains of Elisabeth’s brother Emperor Matthias (1618) and his wife Anna (1619). With the consecration of the Imperial Crypt in the Capuchin Monastery, founded by Empress Anna in 1963 and located at today’s Neuer Markt, the coffins were transferred there in the presence of Emperor Ferdinand from the Queen Monastery. Since then, the hearts of the Habsburgs have been kept separate from their bodies and stored in silver heart-shaped urns in the Heart Crypt of the Augustinian Church.

On January 22, 1592, Queen Elisabeth died at the age of 38. She was described by her contemporaries as dignified, generous, empathetic, with a strong sense of faith, patient and fearful of God, but not bigoted. Furthermore, as Brantome claimed, “she loved her husband very much without being jealous and forgave him for his misdeeds.”

It is fair to say that Archduchess Elisabeth of Austria, Queen of France, was one of the most generous women of her time! She shared her entire wealth and income from France with the people who needed her support. As a result, on the decision of Emperor Joseph II on November 10, 1781 and by decree of January 12, 1782, the Queen Monastery was abolished exactly 200 years after its foundation. As the property could not be sold in one due to its size, and it was not possible to agree on the establishment of a Hotel Garni, it was divided up and auctioned off. In the end, the Viennese Lutheran City Church acquired part and the reformed congregation another.

The remaining property was acquired by Count Fries, a member of the Reformed parish, in order to build his city palace, the Palais Fries and later Palais Pallavicini.

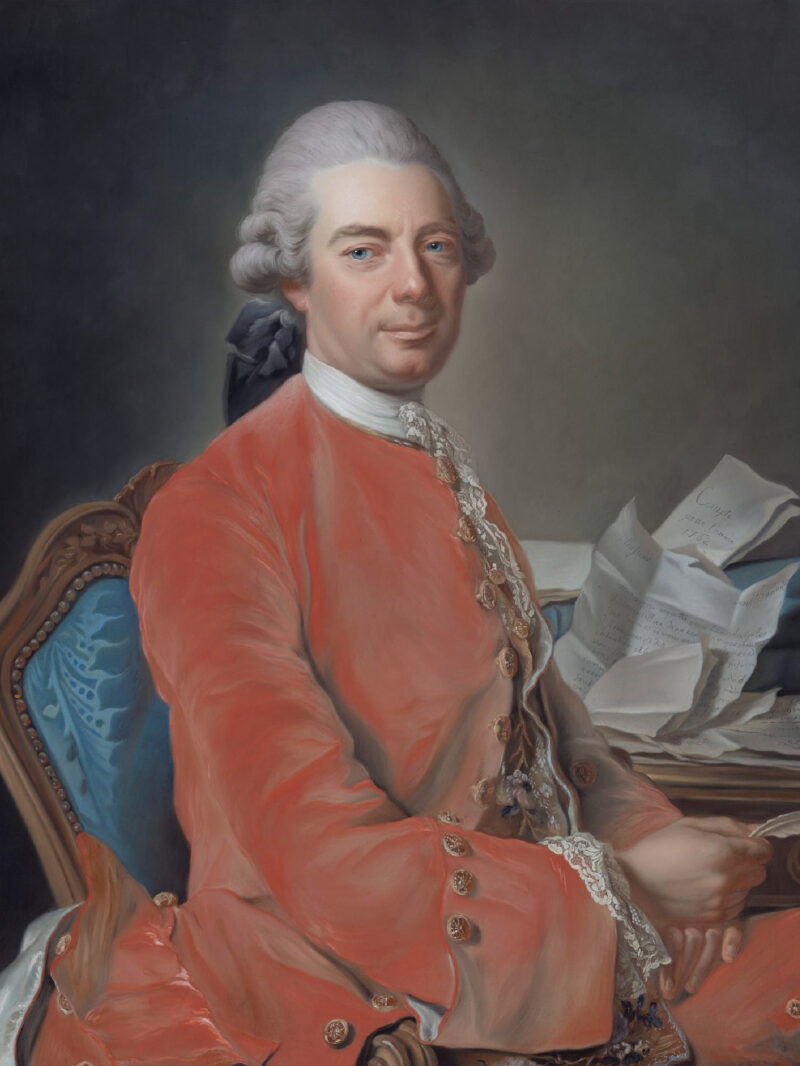

Johann Fries (May 19, 1719 Mühlhausen, France — June 19, 1785 Bad Vöslau, Lower Austria; Calvinist and from 1783 Imperial count) came from a Swiss patrician family and was a councilor of commerce, privy councilor, director of the Imperial silk factories, industrialist and banker. In 1757 he became a knight, in 1762 a baron, in 1771 a court councilor and 1783 he was raised by Joseph II to Imperial count. He was also a member of the Masonic Lodge. During the War of the Austrian Succession, he worked extremely successfully in the service of Austria in the “English Commissary” and in 1748 was entrusted by Wenzel, Prince of Kaunitz-Rietberg, with the delicate task of bringing the outstanding subsidy payments of £100,000, which were denied in England, to Vienna. He achieved this with flying colors in difficult negotiations lasting over a year in London. As a result, Johann Fries was encouraged to join the Austrian service, whereupon Maria Theresia freed him from ‘Staple Rights’ in Vienna in 1751. In 1751, Fries founded various factories: fabric, velvet and silk factories; a brass factory, the “Nuremberg Brass Factory”, and much more.

In 1752 he initiated the “Thalernegoticum” — he received the privilege from Maria Theresia to mint the “Maria Theresien thaler”, which he held from 1756 to 1776. During this period, he delivered 20 million Maria Theresien thalers to the Ottoman Empire and the Levant alone. Johann Fries made sure that the Maria Theresien thaler was recognized as a means of payment from the Orient to Africa. The share that he was allowed to withhold was one third of the seigniorage, a whopping 33.3% of the net profit from the coin’s issue and by placing it on the market.

At that time, Baron Fries was one of the richest men of his time. During the Seven Years’ War with Prussia, he managed the subsidy payments from France of 30 million livres annually, of which he was able to withhold half a percent of commissions. During these years Fries campaigned for the war finances and gave the state significant cash advances, which understandably gave him an even higher status in the Imperial family.

In 1766 Fries and his authorized signatory, Johann Jakob Baron von Gontard, founded the Fries & Co. bank. The Friesische Bank was by far the most important bank house of its time.

On August 29, 1764, Johann Fries married Anne d’Escherny, in Paris, who was from a rich Huguenot family. His first son Franz Josef Johannes was born on September 7th, 1765 and was christened (an absolute novelty and compliment for the Calvinist Fries) in St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna. The godparents were Empress Maria Theresa and her son Emperor Joseph II who were represented by the Imperial colonel that day.

His first daughter Ursula Margaretha Agnes Victoria Ludovica was born on February 3rd, 1767 and he welcomed another daughter Anna Philippina Johanna Sophia on August 11th, 1769. His second-born son, Moritz Christian Johannes (I.), saw the light of day on May 6th, 1777.

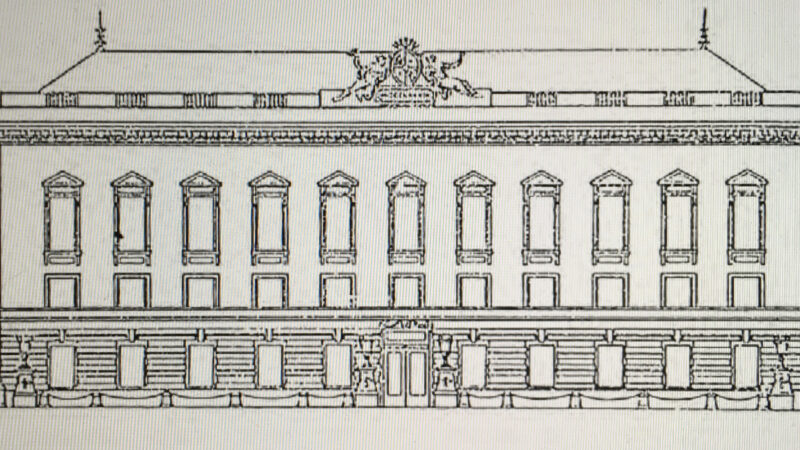

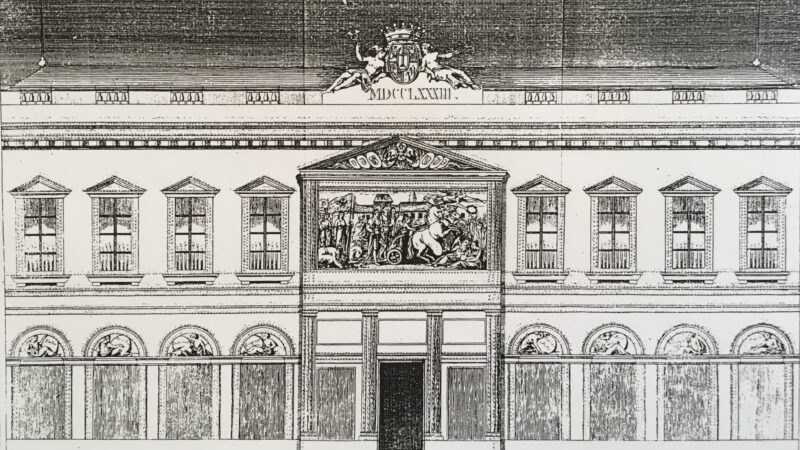

In 1783 – 84 Fries commissioned J. Ferdinand Hetzendorf von Hohenberg, the court architect and creator of the Gloriette and the Palace Theater in Schönbrunn, to build his city palace. His newly acquired property at Josefsplatz was to have its own theater salon, amongst other features.

Before that, Fries had already bought Vöslau Castle in 1761 and had it rebuilt by Hetzendorf and it had aroused admiration in Viennese society. It was also he who brought the Blauer Portugieser grape to Bad Vöslau in 1772 and was thus the founder of Vöslau’s importance as a wine town.

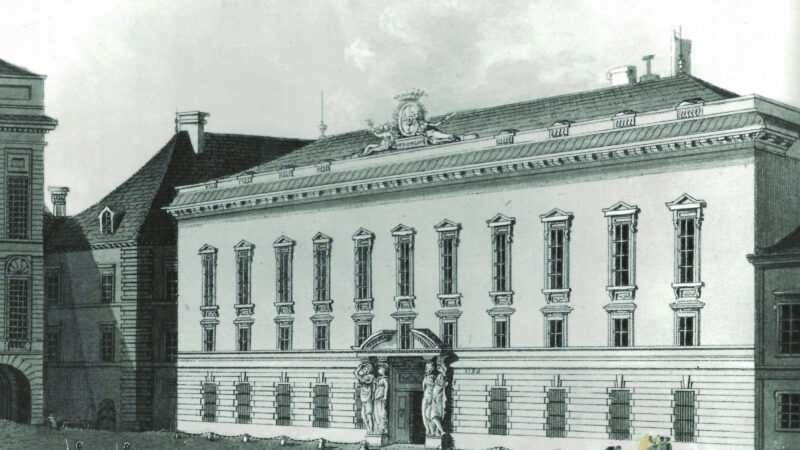

Because of architect Hetzendorf, one of the most interesting and purely classical palace buildings in Vienna was built at Josefsplatz. This building, with its simply designed façade, strikingly modern in contrast to the Hofburg, caused quite a stir at the time.

Only the changes from 1786, which emphasized the design of the main gate, and the attic, which represents the allegories of trade and freedom, brought a lasting change in the original simplicity and filled it with life.

The four caryatids (figures) created by sculptor Franz Zauner, crowned by a blown-up gable, replaced the simple portal, as well as the four stone vases, which stood for the four continents (without Australia) had been met with great criticism. These modificiations in the “baroque style” was a concession to one of the most beautiful, Viennese baroque squares. The vases, Fries then brought to the park of his castle in Bad Vöslau.

When the expensive construction of Fries’ city palace was completed, it became the center of Viennese society. Fries was also a patron and art collector and his role as court and state banker also gave him access to the world of the arts. Baron Fries died on June 19, 1785 in circumstances that have never been fully clarified. People spoke of melancholy and depression and found him drowned in the pond of his castle in Vöslau. A farewell letter was never found.

His eldest son Franz Josef Johannes inherited the huge fortune, which continued to grow under the management of his father’s business partners.

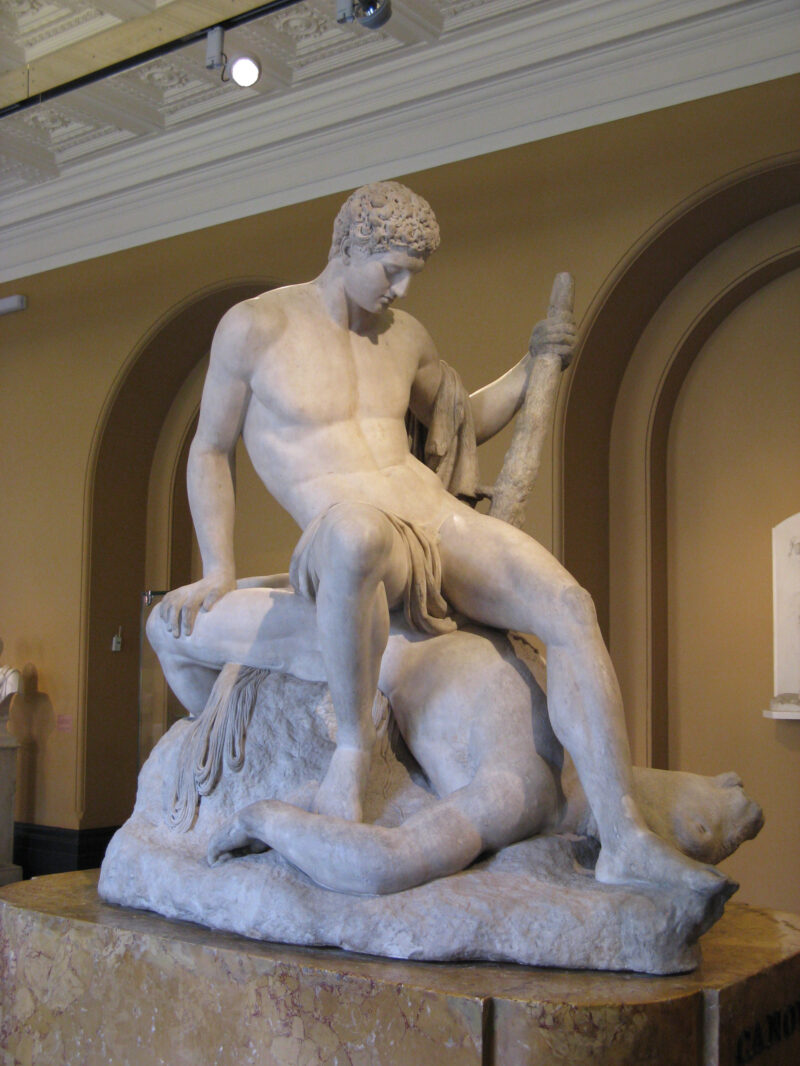

He himself loved to travel, maintained contact with the great artists and intellectuals of his time, such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, whom he met on a trip to Rome. During his travels, he made important art purchases and commissioned work from outstanding artists, such as Angelika Kauffmann and Antonio Canova. In 1787 he brought the group statue “Theseus and Minotaur” from Rome to his palace in Vienna. The weight of this sculpture was about 1.2 tons.

Today this group of figures is owned by the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. With these purchases he laid the foundation for one of the most important art collections in the Habsburg Empire. Franz Josef Johannes Fries fell ill only three years after his father’s death and died in April 1788. His eleven-year-old brother Moritz von Fries inherited the significant family fortune. His guardianship, which not only managed the family wealth, but also increased it, ensured he received an excellent education. At the age of 20 he was introduced to his father’s banking business and was involved in it from that point on.

In October 1800 the distinguished Viennese society gathered for the splendid wedding of Moritz von Fries with the enchanting Maria Theresia Josefa, née princess of Hohenlohe Waldenburg — Schlingenfürst (1779 — 1819). The festivities went on for several days. In the following years, Moritz expanded the already significant art collection of his father and brother by making purchases across Europe and commissioning important artists of the time.

The family’s collection had 300 paintings, including paintings by Rembrandt, Van Dyck, Raffael, Reni, Dürer, and 100,000 engravings and drawings. With 16,000 volumes, the count’s library was also one of the largest in the Habsburg Empire. Furthermore, the house was home to an important collection of sculptures, including works by Canova, and an extensive collection of coins and minerals. At around 1800, the Fries estate had grown to 2.5 million guilders, which made the Imperial Count Moritz von Fries the richest man in the Austrian monarchy. The palace at Josefsplatz became the center of social and cultural life in Vienna. The count invited artists and scholars from many genres to his home, was an honorary member of the Academy of Fine Arts, a founding member of the Society of Friends of Music and patronized many artists of the time.

Fries patronized composers like Franz Schubert — who dedicated the Gretchen am Spinnrade from Goethe’s “Faust” to him in 1814- Joseph Haydn and particularly Ludwig van Beethoven. Beethoven dedicated his 7th symphony in A major, op. 92 (1812), the so-called Fries Symphony, as well as the A minor violin sonata op. 23 (1801), and the F major violin sonata op. 24 (“Spring Sonata”, 1802) to him.

There were many soirees, lavish balls and concerts in Fries’ home, where the most important artists of the day shook hands. One particularly special night at Fries’, in May 1800, Ludwig von Beethoven and the composer Daniel Gottlieb Steibelt met. It resulted in a piano competition between the two, and Steibelt, known for his virtuosity, lost. This scandal subsequently led to the termination of Steibelt’s tour in German-speaking countries.

The sudden descent of the Fries house began in 1817. The many trips and possessions, the feudal lifestyle, and the great devaluation of the Napoleonic Wars all contributed to the decline of this glamorous house. In August 1819, Maria Theresia Josepha, the mother of his six children, died at the age of 41. Fries subsequently married the French dancer Fanny Lombard, with whom he had a daughter.

All attempts to counter the financial difficulties through sales, as well as through new investments, such as the expansion of Vöslau into a thermal bath, were unsuccessful. From 1820 Fries sold a lot of his land off, such as to the Prince of Lichtenstein. Then, in 1823, the valuable art collection was auctioned off and distributed around the world. In 1824, his son Moritz II, along with partner David Parish, took over the heavily indebted bank, ending in Parish committing suicide due to the hopeless situation. In April 1826, the bankruptcy of the Fries bank was declared, providing a topic of conversation for European society. In the following years, the count retired completely from private life in an attempt to preserve a small sense of luxury and travel by selling his personal assets. On December 26, 1826, Imperial Count Fries died alone and poor, away from family and friends, in a Paris hotel. The brilliant rise and the tragic fall of Count Fries is said to have been the model for Ferdinand Raimund’s main character “Flottwell” in “The Wasters”.

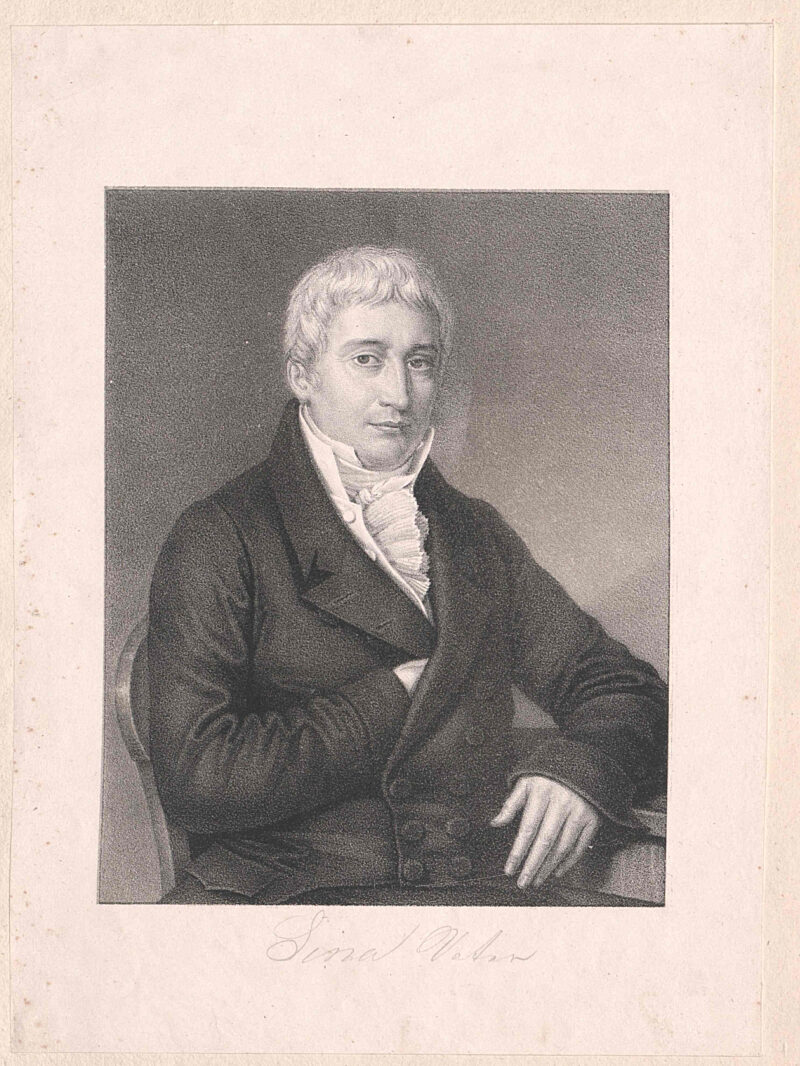

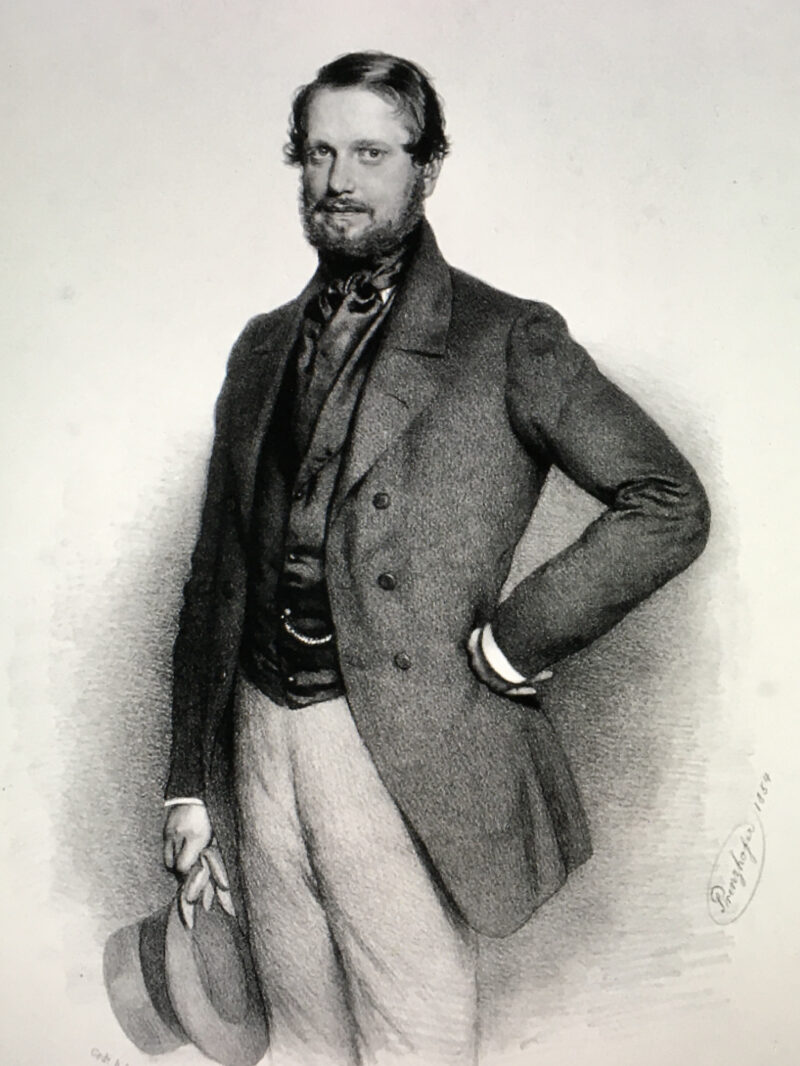

In 1828 his son Moritz Fries II was compelled to sell the palace to his competitor, Count Georg Simon von Sina (1783 — 1856), Baron von Hodos und Kisdia, who, like the Rothschild family, was one of the most important bankers and entrepreneurs.

Georg Simon von Sina came from an important Greek Orthodox family of cotton merchants and invested in tobacco businesses, river shipping, railways, bridge construction (chain bridge over the Danube between Buda and Pest with his friend Count Stephan Széchenyi), the Neusiedler paper mill, and much more.

He was also deputy governor of the Austrian National Bank. In the 1840s, the Sina bank was one of the most important alongside Rothschild and Arnstein & Eskeles. The commercial relations between the wholesale trade and Sina Bank, extended from Vienna to the main trade centers of Europe, such as Paris, London, Rome, but also to Odessa (Odesa), Cairo, Alexandria and even to India. Gaining a Hungarian title (1818), as well as an Austrian knighthood (1826) and being a baron (1832) were also important for Sina. From 1834 – 1856 Sina was the Greek consul general in Vienna and in 1845 he financed, among other things, the observatory in Athens. He also financed the renovation of the Greek church by Theophil Hansen (1813−1891) at the Fleischmarkt in Vienna.

Sina had already bought a palace in Vienna in 1810, at Hohen Markt No. 8, which his son Georg Simon Sina the Younger demolished in 1859⁄60 in order to commission Theophil Hansen with the new building. The building was later bombed in 1945 and burned down completely shortly after. Baron Georg Simon von Sina (1783 — 1856) granted generous loans to the imperial family during the Napoleonic Wars. He was also considered the largest landowner in Hungary and had further assets in Bohemia and Moravia. Due to the high liquidity of the bank, a lot of money was not only invested in the purchase of land, but also in the purchase of real estate. As this was not allowed for Jews in Hungary, it gave the Sina family a significant lead over their Jewish competition.

At that time, Baron Georg Simon von Sina was the largest taxpayer after the Rothschild family in Austria. Sina was the one who brought Theophil Hansen (1813−1891) to Vienna. Later, he was to become one of the most important architects to build on the Ringstrasse.

Georg von Sina left a fortune of around 50 million guilders after his death.

In 1842 his son Georg Simon Sina the Younger finally sold the palace at Josefsplatz to Alfons Pallavicini (1807−1875).

The Pallavicini family belonged to the Italian aristocracy. Originating in northern Italy, the name “von Pallavicini” was first mentioned in documents through Margrave Obertus Pallavicini (1112−1116). He was able to combine his estates, which were between Parma and Piacenza, into “Stato Pallavicini”. They were later assigned to the Duchy of Parma.

A representative for the many influential and outstanding personalities, a member of the Genoese family branch, should also be mentioned here. Agostino Palavicini (1577−1649), the Doge of Genoa and ambassador of the Holy See, masterly portrayed by Anthony Van Dyck — the oil painting is now part of the Getty Museum collection.

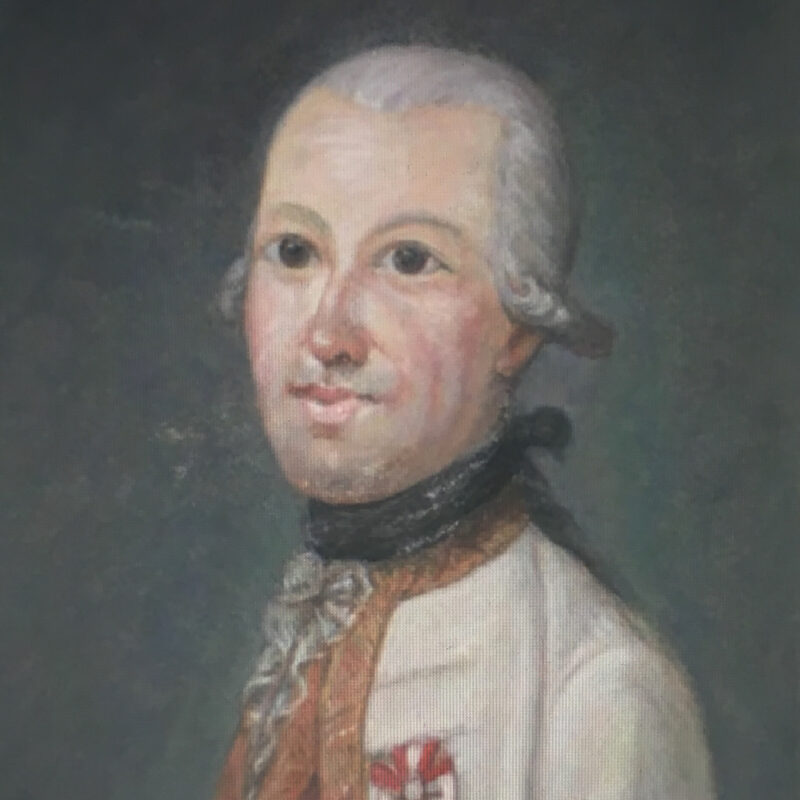

In the second half of the 18th century, Giancarlo Pallavicini (1741−1789) created a line of the Pallavicini family in the Austrian territory. His uncle Gianluca Pallavicini (1697−1773) entered the Viennese court as a diplomatic representative of Genoa to negotiate the difficult situation in Corsica at that time. In 1733 he finally entered the Austrian Imperial service and in the years that followed, he distinguished himself in various political and military functions. It was also he who organized the first navy on behalf of the Imperial family. In 1749 Gianluca Pallavicini was appointed as the commanding general in Italy and in 1754 as the general field marshal. He was subsequently awarded the Golden Fleece for his services to the Habsburg family and he was appointed president of the Milan Council. In 1768 he was entrusted with the honorable task of accompanying the Archduchess Maria Carolina on her trip to Sicily, which clearly highlights the reputation he had acquired over the years. Gianluca, who became patron of the arts, found his last home in Bologna.

In the year 1770 he supported the Mozart family and held a lavish party to their honor in his city palace at 28 Via Aurelio Saffi. It was he who gave them valuable contact with Cardinal Lazzaro Pallavicini in Rome.

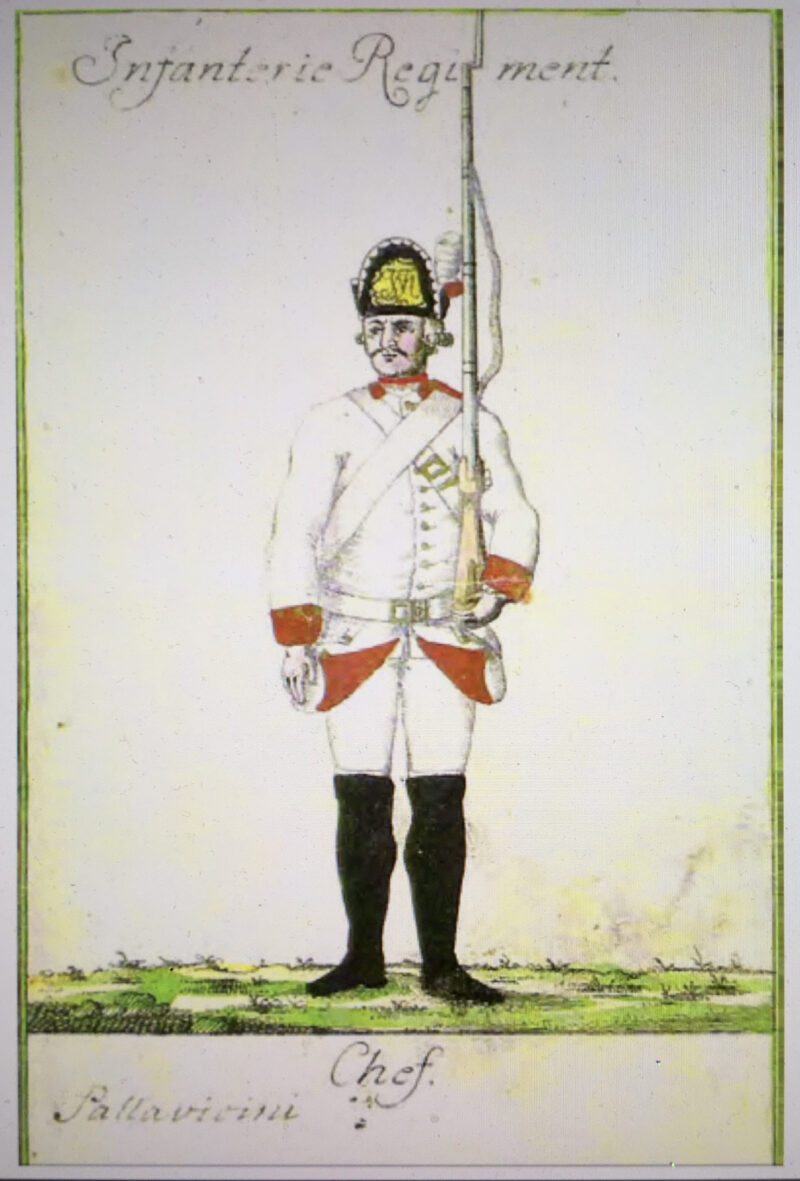

His nephew, Giancarlo Pallavicini (1741−1789) and founder of the Austrian line, followed in his footsteps in the second half of the 18th century. He was involved in many battles for the Austrian Imperial family, for which he received numerous awards and promotions. On May 1, 1773, he was appointed as supreme commandant of the Pallavicini Regiment and the most notable battles in which he was involved were those against the Ottoman Empire.

At the end of his career he was appointed as the head of Archduke Karl Stephan’s 8th Infantry Regiment, where he fought the Turks for the last time and succumbed to injury.

Eduard Pallavicini (1787−1839) subsequently elevated the position of the Pallavicini family through the purchase of Hungarian assets and was awarded Hungarian citizenship and nobility rights in 1803, as well as the Bohemian and Moravian rights and the Fideikommiss in the Austrian Hereditary Lands. Marriages with members of influential families from the Austrian Hereditary Lands, such as Zichy, Széchenyi, Hardegg or Fürstenberg, also strengthened the Pallavicini family’s position in the Habsburg Empire.

In 1842 Alfons sen. Pallavicini (1807−1875) finally bought the palace at Josefsplatz from Baron von Sina and had it rebuilt and modernized in 1842 – 45 in the style of the second Rococo. The ceremonial and ball rooms were redesigned in 1843 by the architect Franz Beer in the neo-rococo style.

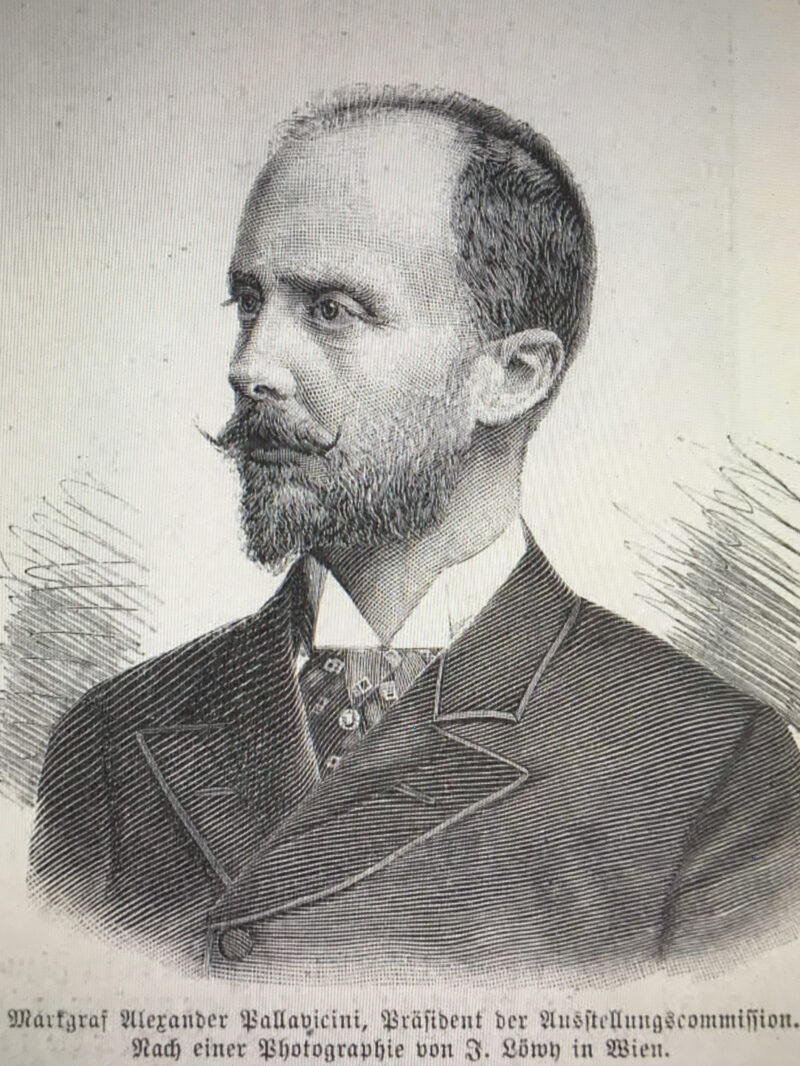

Alfons sen. Pallavicini also received the margrave title in the Austrian territory in 1868. He was also a member of the upper house of the Hungarian parliament, k.u.k. commander and secret councilor, member of the Order of Malta, the Order of the Golden Fleece and Knight of the Order of the Iron Crown. Margrave Alexander sen. Pallavicini (1853−1933) subsequently inherited the palace from his father Alfonso in 1873.

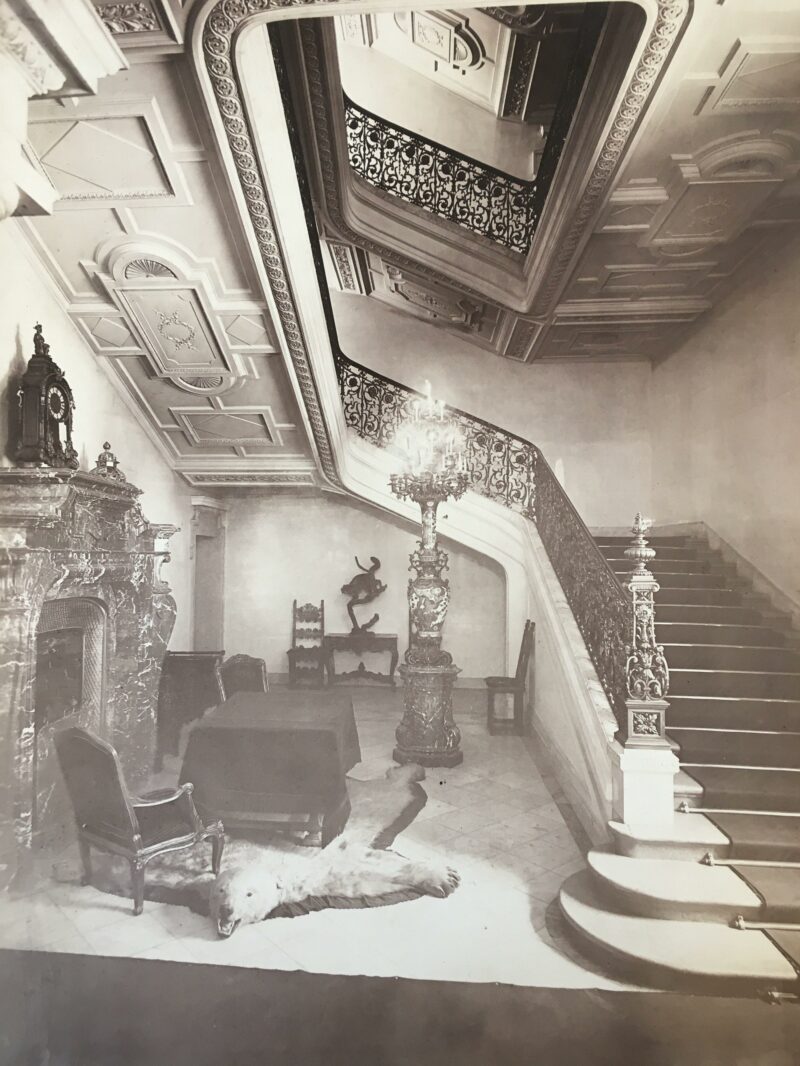

In the same year he had the staircase of the palace and the entrance area remodeled in the style of historicism and the stairwells furnished with Imperial stone.

Margrave Alexander sen. Pallavicini was also a member of the upper house in the Hungarian parliament, k.u.k. commander and secret councilor, member of the Order of Malta, the Order of the Golden Fleece and Knight of the Order of the Iron Crown.

In June 1876 he married the lady of the palace and bearer of the Star Cross Order, Irma Countess Széchényi (1855−1932) and had three sons with her, Karl, Alfons and Alexander jun. Pallavicini.

The state rooms of Palais Pallavicini have always been a place of festive and cultural activities. The salons reflect the baroque joie de vivre artists and the “who is who” of Viennese society at the time came and went, and lavish festivities were celebrated.

The Pallavicini family has owned the palace for over 150 years. It was Margrave Karl Pallavicini, the father of the current owners of the palace, Alfonso and Eduardo Pallavicini, who brought the palace through the turmoil of the Second World War and thus ensured the preservation of the palace until the 21st century.

As one of the last family-owned city palaces, it is still lovingly cared for and maintained by the family.

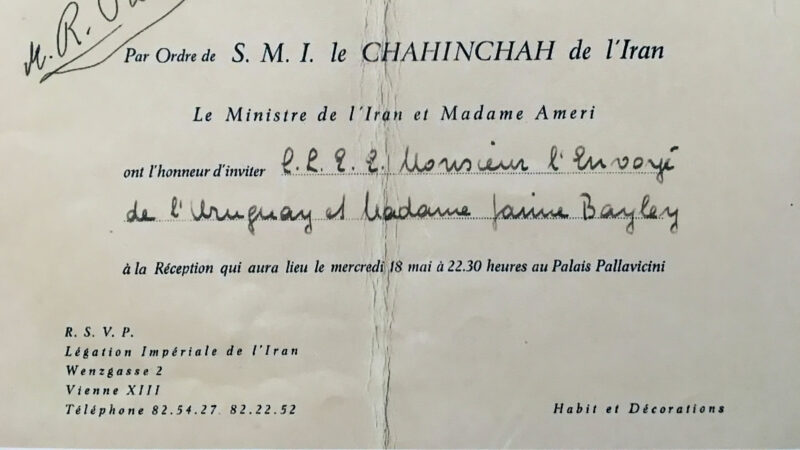

Even in the 20th century, both the international aristocracy and high society were guests at lavish events, such as the Shah of Persia or Jacky Kennedy who met Mrs. Khrushchev at a luncheon held in their honor at the Palais Pallavicini in 1961. The Presidential Museum in Boston showcases a photograph with following charming quote of Jacky Kennedy: “Mrs. Khrushchev was very shy at the palace (Pallavicini) in Vienna where we had lunch. There was this protocol thing. For some reason, I outranked her because Jack was President and Khrushchev was just Chairman (of the Council of Ministers)…so she wouldn’t leave the room before I did. And I didn’t like to go before an older woman and…she was so hanging back, and…finally I said — in desperation I took her by the hand and said, well, I’m very shy so you’ll have to come with me.”

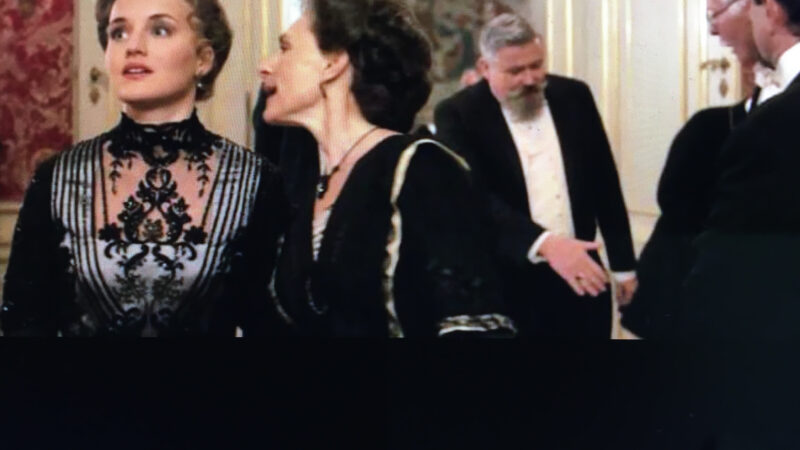

Many elegant celebrations, weddings and receptions are still held in the magnificent ballrooms.

From the second half of the 20th century, the palace in downtown Vienna also served as a film set for international and Austrian cinema and television films.

One of the most important films in post-war history was shot here, “The Third Man”. This brilliant spy movie, that was produced in Great Britain in 1949, based on the screenplay by Graham Greene and directed by Carol Reed, starring Orson Welles, Joseph Cotten, Paul Hörbiger, Anni Rosar and music with which it became world famous by Anton Karas.

Awards and nominations were:

International Cannes Film Festival 1949

Grand Prix British Film Academy Award 1950

Best British film

Best Film nomination

Academy Awards 1951

Oscar in the category Best Black and White Camera to Robert Krasker

Nominations in the categories Best Director and Best Editor

More recent awards include:

2013 “The Devil’s Violinist” about Niccolò Paganini “directed by Bernhard Rose with David Garrett

2016 the film “Das Sacher” about Anna Sacher by the Austrian director Robert Dornhelm

2019 “Vienna Blood” directed by Robert Dornhelm and Umut Dag

I would like to end my journey through time with the words of a contemporary witness of Princess Nora Fugger from her biography “In the Splendor of the Imperial Age”:

“But no one should believe that I thought of all these certainly very interesting historical things when we — as always,

the last ones — entered the wonderful dance hall of the Palais Pallavicini.

Margrave Sandor Pallavicini and his wife graciously made the honors.

Margravine Irma was one of the most impressive figures in Vienna.

With her stunning family jewelry and her splendid shape, she impressed everyone who entered.

The celebrations in the palace at Josefsplatz were particularly popular. Everything oozed sophisticated elegance .…..”

Sources:

Steeb, Christian. „Die Grafen von Fries“, Hrsg. Stadtgemeinde Vöslau 1999 (auf Grundlage der gleichnamigen Dissertation des Autors „Die Grafen von Fries. Eine Schweizer Familie und ihre wirtschaftspolitische und kulturhistorische Bedeutung für Österreich zwischen 1750 und 1830“)

Roth, Franz Otto: „Zur feierlichen Besitzübernahme von Deutschlandsberg, Feilhofen, Frauental und St. Andrä im Sausal anno 1812.“ (Zeitschrift des historischen Vereines LXII Jg. Graz 1971)

Otruba, Gustav: „Fries, Moritz Graf von“, in: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 5, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1961, S. 606

Fries, Moritz Christian Graf. In: Österreichisches Biographisches Lexikon 1815 – 1950 (ÖBL). Band 1, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Wien 1957, S. 367.

Czeike, Felix: „Wien. Kunst und Kultur-Lexikon. Stadtführer und Handbuch“, Süddeutscher Verlag München 1976, S. 87

Czeike, Felix: „Wien. Innere Stadt. Kunst- und Kulturführer“, Wien: Jugend und Volk, Ed. Wien, Dachs-Verlag 1993, S. 98

Harrer-Lucienfeld, Paul: „Wien, seine Häuser, Menschen und Kultur. Band 6, 2. Teil“, Wien 1957 (Manuskript im WStLA), S. 313 – 315; 321 f.

Schmidt, Justus/Tietze, Hans: Dehio Wien. Wien: A. Schroll 1954 (Bundesdenkmalamt: Die Kunstdenkmäler Österreichs), S. 77 f.

Kobald, Karl: „Klassische Musikstätten“, Zürich/Leipzig/Wien Amalthea — Verl.

1929, S. 105 ff.

Blauensteiner, Kurt: „Gerards Bildnis des Reichsgrafen Fries“, in: Jahrbuch des Vereins für Geschichte der Stadt Wien, 1939 – 1989 Band 2, 1940, S. 121 ff.

Markl, Hans: „Kennst du alle berühmten Gedenkstätten Wiens?“ Wien [u.a.]: Pechan 1959 (Perlenreihe, 1008), S. 41

Kisch, Wilhelm: „Die alten Straßen und Plätze von Wiens Vorstädten und ihre historisch interessanten Häuser“, Photomechan. Wiedergabe d. Ausg. v. 1883, Cosenza: Brenner 1967, Band 1, S. 264ff.

Gugitz, Gustav: „Bibliographie zur Geschichte und Stadtkunde von Wien“, Hg. vom Verein für Landeskunde von Niederösterreich und Wien. Band 3: „Allgemeine und besondere Topographie von Wien“, Wien: Jugend & Volk 1956, 340f. (Friespalais)

Salzer, Monika/Karner, Peter: „Vom Christbaum zur Ringstraße. Evangelisches Wien“, 2., verbesserte Auflage, Wien 2009, S. 68 – 70

http://www.architektenlexikon.…

Pulle, Thomas: Untersuchungen zum Palais Fries am Josefsplatz, im Kunsthistorischen Institut Wien, Aufnahmearbeit, eingereicht im Wintersemester 1987⁄88

Clary-Darlem (Mme.), Elisabeth d’Autriche, reine de France (Paris et Leipzig 1847, 8°.). – Papyre-Masson (Jean), Entiérs discours des choses qui se sont passées à la réception de la reine et mariage de Charles IX. (Paris 1574, auch 1615, 8°.). – Pinart (Louis), Veritable discours du mariage de très-haut, très puissant et très-chrétien roi Charles IX. et de la très excellent et vertueuse princesse, madame Elisabeth, fille de l’empereur Maximilien II. fait et célébré à Mézières le 26me jour de Novembre 1570 (Paris 1570, Fol.) [wiedergedruckt im „Ceremonial de France“ von Theodor Godefroy (Paris 1649, Fol.) Bd. II, p. 20]. – Martonne (Alfred de), Isabelle d’Autriche (Paris 1848, 8°.). – Discours de la vie de la reine Isabelle, fille de l’empereur Maximilien (Paris 1592, 8°.). – Außer den bisher angeführten selbstständigen Quellen sind noch zu nennen: Brantôme, Vie des Dames illustres. Ausgabe von Monmerqué. – De Thou (J.), Historiarum sui temporis libri CXXXVII, im XLV. und XLVIII. Buche. – Fontette et Lelong, Bibliotheque historique de la France, tom. II, part. 3me., chap. 4, art. 2 – 3; – chap. 7, art. 7, pag. 20, 702, 713, 717, 837. – Capefigue, Mémoires des Reines et Regentes de France. Tome Vme.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/…

Sammlung von Bildern, Videos und Audiodateien

Bildquelle Tor des Palais : Wilhelm Kitsch Wien Gottlieb 1883

Benvenuto Cellini Salzfass, sog. “Saliera”, hergestellt 1540 – 1543 in Paris. Gold, teilweise emailliert; Sockel: Ebenholz. Heute im Kunsthistorischen Museum Wien

Portrait Lithographie von Freiherr von Sina: von Kaufmann Handel — http://www.bildarchivaustria.at/Pages/ImageDetail.aspx?p_iBildID=8150849, Gemeinfrei, https://commons.wikimedia.org/…

Stehende Lithogr. Von Freiherr von Sina Von August Prinzhofer — Eigenes Foto einer Originallithographie (N.G.Graz), Foto: Peter Geymayer, gemeinfrei, https://commons.wikimedia.org/…

Familyarchive Pallavicini