Buddhist House Altar

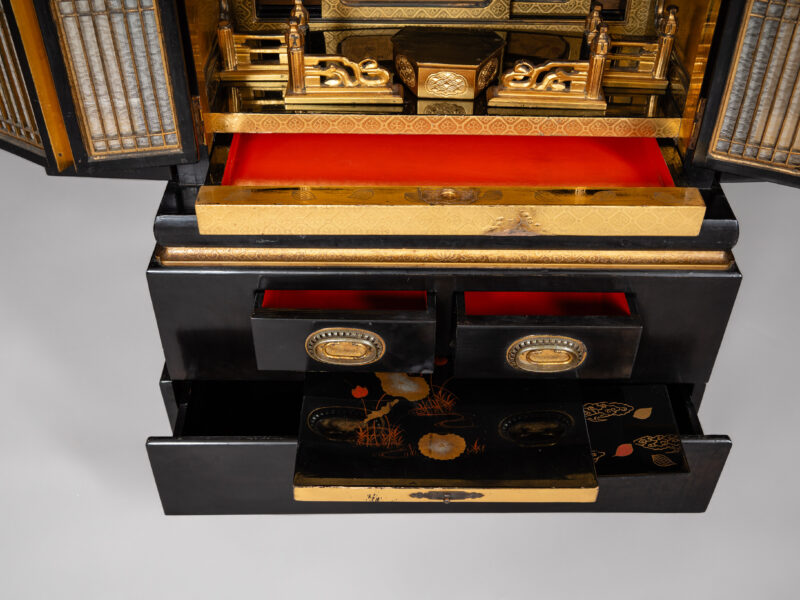

Beautifully executed Japanese house altar in black and red lacquered finish.

This splendid shrine features various drawers, pull-outs, sliding doors, as well as two full folding double doors and two folding lattice doors, all adorned with a fine original fabric.

The double doors reveal a radiant, gold leaf-adorned interior. The shrine is magnificently gilded with rich carvings and colorful finishes. At its center stands a finely carved Buddha, atop an ornate pedestal crowned with a lotus blossom. Inside the shrine, there are various utensils such as hanging lanterns, incense stick holders, candle holders, and a tablet.

Noteworthy, besides the small figurative representation in the upper section and the colorful painting, is the exceedingly elaborate pagoda roof, consisting of hundreds of pieces. Altars of this kind were traditionally crafted almost entirely without screws or nails, employing a very intricate interlocking method.

The present Butsudan is in beautiful condition with a fine patina, though the small Buddha sculpture is missing its right hand.

History of the Butsudan:

The precursor to the Butsudan was a portable shrine containing Buddhist images, where statues and tables were only set up when in use.

By order of Emperor Temmu in 686, every household was to possess its own altar.

The use of private household altars became widespread during the Muromachi period (1336 – 1573), particularly through the Jodo Shinshu tradition, which issued calligraphies with the invocation “Namu Amida Butsu” and established precise rules for their handling.

The belief that the altars carried by traveling “holy men” or “hijiri” (聖) possessed special powers surely contributed to their dissemination as well. Japanese household altars, modeled after the grand examples found in Buddhist temples, primarily served for the veneration of Buddha and the commemoration of ancestors, to whom offerings were made and Buddhist sutras were read.

There are fundamentally three forms of household altars, some of which date back to the Edo period.

The Karaki Butsudan (唐木仏壇), particularly common in Zen traditions (禅宗), was made of precious woods such as ebony or red sandalwood.

The Kin Butsudan (金仏壇), mostly used in the Jodo school (浄土宗), featured interior gilding.

The Kagucho Butsudan (家具調仏壇), due to its tall structure, best combines with Western furniture styles.

In a Japanese Butsudan, we find the Honzon (本尊), or main object of veneration, and the Butsugu (仏具), ritual objects.

On the three main levels of the altar, the objects are arranged from top to bottom according to their importance. The topmost level always contains the main object of veneration, which can vary depending on the tradition. It was usually a Buddha figure, or a calligraphy, as in the case of the Nichiren school (日蓮宗).

The “koji” (脇侍), representations flanking the Buddha on both sides, often depict the founders of the lineage. For example, the Honzon in the Sotoshu altar consists of Buddha Shakyamuni in the center, flanked by Keizan and Dogen on the left and right. Sometimes, hanging lanterns called “tsurikoro” (吊灯籠) that illuminate the Honzon, as well as garland-like decorations or “yoraku” (瓔珞), are also present. The “ihai” (位牌), ancestral tablets bearing the posthumous Buddhist names of the deceased, are placed either to the left and right of the Honzon, or on a level below. It is not customary in every tradition to place Ihai in Butsudan and was probably adopted from Confucianism.

The Butsugu, as ritual objects, are located on the lower steps of the household altar. Typically, these are the five traditional offerings – candles, incense, flowers, food, and water.

On the middle level are the “takatsuki” (高坏) – stands for food offerings and bowls for tea and water offerings. The food is practically never discarded but consumed by the household members. Those who do not wish to offer food daily before family meals opt for durable offerings. On the lower level are flowers, candles, and the incense burner, considered minimal requirements for the altar. These items are placed on brocade cloths. The “uchishiki” (打敷), a triangular cloth, hangs down at the front. Often, the official symbols of the Buddhist tradition are attached to these cloths.

These cloths are said to date back to the time of the historical Buddha and symbolize the fabric offered to him as a seat.